After visiting

Midyat we wandered down to

Mor Gabriel Monastery, twelve miles southeast of Midyat and fifteen miles north of the Syrian border. Here, at least, Syriac Christianity appears to be surviving. This is one of the oldest monasteries in the world. It was founded in 397 by Mor (saint) Samuel (d. 433) and Mor Simon (d. 409). Originally it was called the Monastery of Mor Samuel and Mor Simon, but in the seventh century it was renamed Mor Gabriel Monastery after

Mor Gabriel (634-668), the bishop of the

Tur Abdin Region. Except for brief periods during wars and civil disorders the monastery has operated continuously since the year 397. Visitors are not allowed to wander around the grounds by themselves (although you can stay overnight if you make previous arrangements), but a guide is provided to give you a tour. Our guide, a young Syriac Christian, spoke perfect, unaccented English.

Entrance to the monastery (click on photos for enlargements)

Entrance to the courtyard

Inner courtyard of the monastery

Monastery grounds

Steeples

Circular Room. The small windows on the dome open on monks’ cells.

Our guide related that Theodora was born near here, in what is now Syria, and that her father was a Syriac priest. It was this connection with the area and the Syriac Church that motivated her to make a sizable donation to the monastery for the purpose of building this room. This is the sanitized version of Theodora’s background. Most sources do agree that she was born in Syria, but many maintain that Theodora was the daughter of a bear trainer and a professional dancer and actress. They began pimping out Theodora and her sister Komito when they were both pre-adolescents. Theodora quickly began one of Constantinople’s most notorious prostitutes.

If we are to believe the Byzantine historian Procopius (c. AD 500 – c. AD 565), who probably knew her personally, Theodora engaged in behaviour which would make even Kim Kardashian blush:

One night she went into the house of a notable during the drinking, and, it is said, before the eyes of all the guests she mounted the protruding part of the couch near their feet and forthwith pulled up her dress in the most disgraceful manner, and did not shy away from displaying her lasciviousness. And though she made full use of three orifices, she often found fault with Nature, complaining that Nature had not made the holes in her nipples larger so that she could devise another variety of intercourse there. Of course, she was frequently pregnant, but by using pretty well all the tricks of the trade she was able to induce an immediate abortion. Often in the theatre too, in the full view of the people, she would throw off her clothes and stand naked in their midst, having only a pair of knickers over her private parts and her groin – not, however, because she was ashamed to expose these also to the public, but because no one is allowed to appear there absolutely naked: underwear over the groin is compulsory. And with this costume she would spread herself out and lie on her back on the floor. Certain menials on whom this task had been imposed would sprinkle barley grains over her private parts, and geese trained for the purpose used to pick them off with their beaks one by one and swallow them. Theodora, far from blushing when she stood up again, actually seemed to be proud of this performance. For she was not only shameless herself but did more than anyone else to encourage shamelessness. And many times she threw off her clothes and stood in the middle of the actors on the stage, leaning over backwards or pushing out her rear to invite both those who had already enjoyed her and those who had not been intimate as yet, parading her own special brand of gymnastics. With such lasciviousness did she misuse her own body that she appeared to have her privates not like other women in the place intended by nature but in her face! And again, those who were intimate with her showed by so doing that they were not having intercourse in accordance with the laws of nature, and a person of any decency who happened to meet her in public would swing round and beat a hasty retreat, for fear he might come into contact with any of the hussy’s garments and so appear tainted with this pollution. For to those who saw her, especially in the early hours of the day, she was a bird of ill omen. (Quoted from Procopius’s Secret History)

None of this mattered to Emperor Justinian, who became besotted with Theodora and eventually married her. As the wife of a Byzantine emperor Theodora might well have wanted to upgrade her image by donating money to religious institutions. Thus she has been memorialized here at Mor Gabriel Monastery. Justinian himself initiated the construction of

Aya Sofia in Istanbul, to this day one of the most magnificent religious structures in the world. Maybe he was feeling guilty about marrying a nymphomaniacal

prostitute and wanted to do something to atone for it?

Theodora (c. 500 – 28 June 548) portrayed on a mosaic in a church in Ravenna, Italy (not my photo)

This was probably the dining hall in the monastery

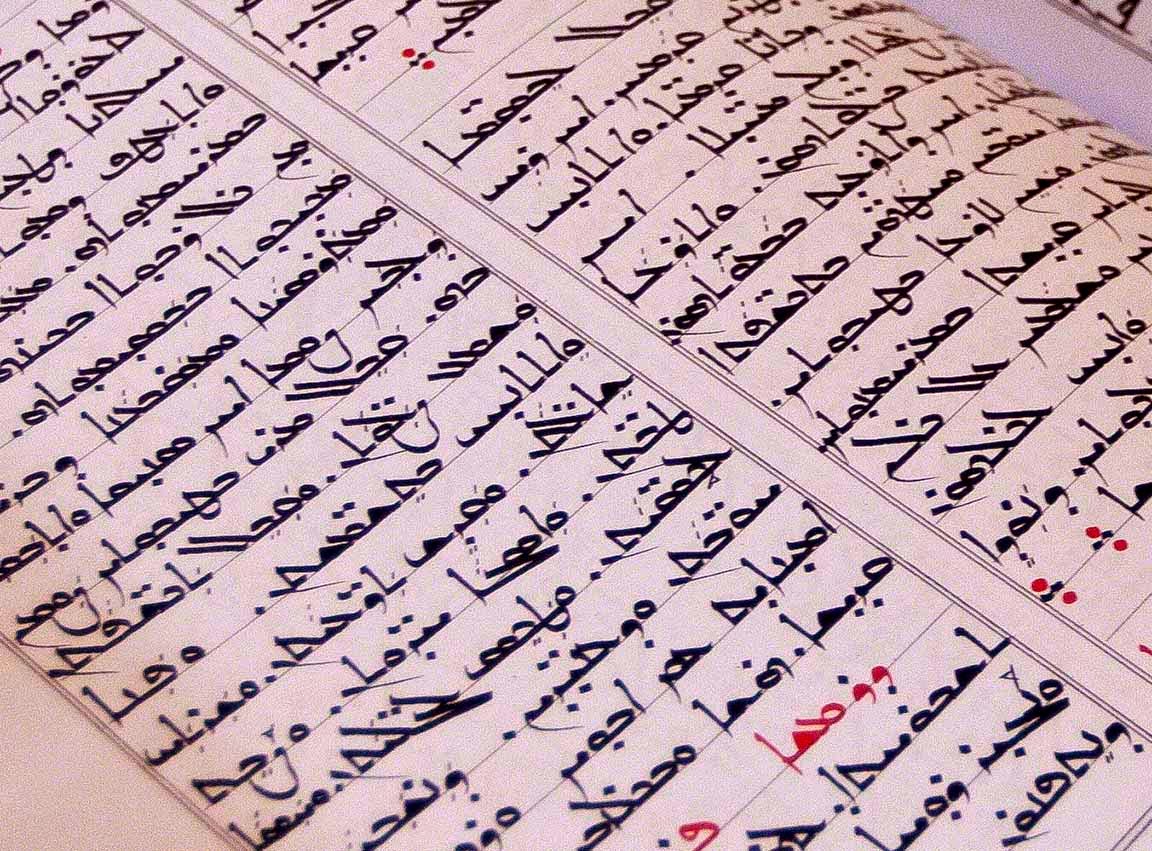

A book, I believe a Bible, but I am not sure, in Syriac Script. The

Syriac Language is closely related to Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus of Nazareth, leader of the

Galileans.

Closer view of Syriac Script.

A Syriac inscription on a wall in the monastery

New addition to the monastery. Local stone carvers and masons have lost none of their traditional skills.

Good example of local stonework