Thursday, November 30, 2023

Iran | Yazd

Tuesday, September 26, 2023

Saturday, September 2, 2023

Turkey | Mardin | Deyrulzafaran Monastery

Deyrulzafaran Monastery is located about three and half miles from downtown Mardin. Every travel agent in town offers a stop at the monastery on one their tours of the local sites, but there does not seem to be any public transportation. A taxi costs 25 lira ($11.77), which seemed rather exorbitant. I tried to bargain the price down to 20 lira with several different taxi drivers but to no avail. The last one got a bit huffy and unleashed a barrage of Turkish at me that didn’t seem all that friendly. So I decided to walk. If I can’t walk three and a half miles in an hour it is time to hang up my walking cane. At ten in the morning it was still fairly cool and the walk out of town went quickly. I soon arrived at the turnoff to the monastery at the village of Eskikale. From here it about a mile to the monastery through sparsely vegetated hills inhabited by flocks of sheep and the occasional horse and frolicking colt.

Outside of the monastery were half a dozen big tour buses, dozen or more minivans with tour groups, and a sprinkling of private vehicles. Just outside of the monastery grounds is a new visitors center with an extensive gift shop and a cafe with abundant patio seating. After quaffing down two liters of water I bought a six lira ticket and entered the monastery.

Deyrulzafaran is one of the oldest monasteries in the world. It was founded in 439 on the site of a former sun-worshippers’ temple, as was the Mor Behnam and Mort Sara Church. Unfortunately only the main courtyard and several rooms fronting on it, including a small chapel, are open to the public.

Deyrulzafaran Monastery (click on photos for enlargements)

Deyrulzafaran Monastery

Main entrance to Deyrulzafaran Monastery

Gateway leading to the inner courtyard

The inner courtyard

The inner courtyard

Walkway fronting on the courtyard

Walkway fronting on the courtyard

Dining Hall in the monastery

Chapel in the monastery

View of the plains of Mesopotamia from the monastery

It was quite a bit warmer by the time I started walking back to Mardin. I did not have a hat, and the sun was uncomfortably hot on my head, freshly shaven just this morning. I was just about out of steam by the time I reached the main road back to Mardin. Maybe it was time for me to hang up my walking cane. Then a car stopped. Inside were three downright gorgeous women who looked to be in their twenties or early thirties. The driver asked me in a sexy French accent if I needed a ride. For a moment I thought I might have stepped into a scene in some risqué French movie. Did these women drive around country roads picking up men and ravishing them? Were these women about to ravish me? No, as it turned out. The driver explained that she and her friends were from France but working in Istanbul. They had flown to Mardin the evening before, rented a car, and were taking in the sights. They planned to fly back to Istanbul tonight. They were now on their way to Midyat. We drove to the edge of town and they dropped me off at the cutoff to Midyat. Back in the Mardin town square I saw one of the taxi drivers who had turned down my offer of 20 lira earlier. “Manastir—yirmi besh! (monastery—twenty-five lira),” he offered, I held out my ticket stub to the monastery and made walking motions with my fingers. He snorted, clearly not believing I had walked to the monastery and was back in time for lunch.

Sunday, August 6, 2023

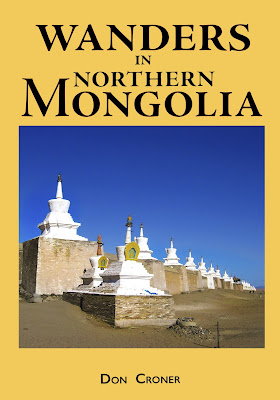

Mongolia | Wanders in Northern Mongolia

Excerpts from Wanders in Northern Mongolia:

Mongolia | Wanders in Northern Mongolia

Excerpts from Wanders in Northern Mongolia:

Chingis Khan Rides West

Chingis Khan Rides West examines the motivation behind Chingis Khan’s ride westward to attack the Islamic world and recounts the fall of the great Silk Road cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, Termez, Gurganj, and others.

Hungary | India | Shambhala | Csoma de Körös

Csoma de Körös was a full-blown eccentric who devoted his entire life to the pursuit of arcane knowledge. As the Russian theosophist and fairy godmother of the New Age movement Madame Helena Blavatsky noted, “a poor Hungarian, Csoma de Körös, not only without means, but a veritable beggar, set out on foot for Tibet, through unknown and dangerous countries, urged only by the love of learning and the eager wish to shed light on the historical origin of his nation. The result was that inexhaustible mines of literary treasures were discovered.” Among the written works unearthed were the first descriptions of the Buddhist realm of Shambhala to reach the Occident.

Körösi Csoma Sándor, later better known as Alexander Csoma de Körös, was born in Hungary on 4 April 1784 to a family of so-called Szeklers, a semi-military caste of the Hungarian Magyars who considered themselves descendants of Attila’s Huns. For centuries they had guarded the frontiers of Transylvania against the non-Christian Turks to the south. Csoma was expected to take up management of the family estate but at an early age began exhibiting symptoms of wanderlust . . . See Eccentric Hungarian Wanderer–Scholar Csoma de Körös and the Legend of Shambhala.

|

| Tomb of Csoma de Körös in Darjeeling, India |

Friday, October 15, 2021

Uzbekistan | Khorezm | Nukus | Fifty Forts Region

From Khiva I wandered on down the Amu Darya River (also known as the Oxus) to the city of Nukus. Actually I did not want to go to Nukus. I was much more interesting in the ruins of the old Silk Road cities and fortresses scattered along the north bank of the Amu Darya, but my driver insisted that all tourists who come this way go to Nukus to visit the Karakalpakstan State Museum of Art. Unfortunately he did not point out why all tourists go to the Karakalpakstan State Museum. It turns out, according to A Recent Story In The New York Times, that this “museum in the parched hinterland of Uzbekistan . . . is home to one of the world’s largest collections of Russian avant-garde art.”

I did not know this at the time. I did peek through a few doorways into galleries containing what looked like avant-garde art, but of course I did not go in, since I have not the slightest interest in anything avant-garde and indeed little interest in any art created since the fall of the Ottoman Empire. I did spend an enjoyable couple of hours examining the museum’s fair to middling collection of Zoroastrian Ossuaries, which was especially interesting to me since I had just recently visited a Zoroastrian Tower of Silence, also on the banks of the Amu Darya, where human corpses were stripped of their flesh so their bones could be collected and placed in funeral urns like these. I also drooled over the museum’s small but mouth-wateringly delectable collection of antique Turkmen Carpets.

But enough of that. From Nukus we proceeded eastward along the northern bank of the Amu Darya through what is known as the Ellik Kala, or Fifty Forts Region. The area is dotted with ruins of cities and forts dating from perhaps the third or fourth century BC to the seventh century AD. At one time many of these settlements would have served as important way-stations on the Silk Road between Bukhara and Samarkand to the east and Kunya Urgench, farther on down the Amu Darya.

Kyzyl Kala (Fortress)

Ruins of Toprak Kala, dating to about 2000 years ago

Ruins of Toprak Kala

Ruins of Toprak Kala

Ruins of Toprak Kala

Ruins of Toprak Kala

Aerial view of the ruins of the lower fortress of Ayaz Kala. Built sometime in the 4th–7th centuries AD, the fortress may have been destroyed during the Mongol Invasion of Khorezm in the 1220s (see Enlargement). The ruins of the old city can be seen to the left of the fortress.

Ruins of the lower fortress of Ayaz Kala

Ruins of the lower fortress of Ayaz Kala

Ruins of the lower fortress of Ayaz Kala

Just north of the Lower Fortress on a higher summit is another larger fortress dating back to the 4th century BCE.

Aerial View of Upper Fortress (see Enlargement)

Ruins of the upper fortress of Ayaz Kala

Ruins of the upper fortress of Ayaz Kala

Ruins of the upper fortress of Ayaz Kala

Thursday, October 14, 2021

Uzbekistan | Khwarezm | Mizdakhan | City of the Dead

Mazlum Sulu Khan was supposedly the beautiful daughter of the governor of Mizdahkan. Despite being desired by all of the local eligible bachelors, Mazlum Sulu Khan was in love with a poor builder. Frustrated by the lack of a suitable groom, the governor foolishly announced that he would give his daughter’s hand to the young man who could build a minaret as tall as the sky in the space of one night. Naturally the poor builder succeeded in constructing the minaret, but when he came to the palace for the hand of his bride the following morning, the governor refused. The dejected young man jumped from the top of the minaret only to be followed by the beautiful and distraught Mazlum Sulu Khan. The heartbroken governor ordered that the minaret be destroyed. The young lovers were buried together and a mausoleum was constructed above their grave using the bricks from the ruins of the minaret.